‘A wonderful memoir . . . a great example of how to wrest real life into a work of art’

Jonathan Coe, Guardian

‘The most disturbingly vivid fast-track into childhood’s unexpressed hugeness, that I have come across . . . fiction cannot compete with this’

Joanna Murray-Smith, Melbourne Age

‘Every morning, first thing, Derek Cross used to beat the dog. He liked things neat, and dogs like the one he had given his stepson, the author of this remarkable memoir, mess things up . . . Cross has given his own life story the shapeliness and ironic depth of fiction’

Sunday Times

‘Straight from the heart. Quite simply it cannot be faulted’

Big Issue

‘It is the relentless prosecution of Derek that truly ignites the book . . . The way Cross puts the authorial boot in, tears shining in his eyes, is riveting’

Independent on Sunday: read the full review

‘Moving and engrossing . . . Heartland is a tour de force’

Daily Mail

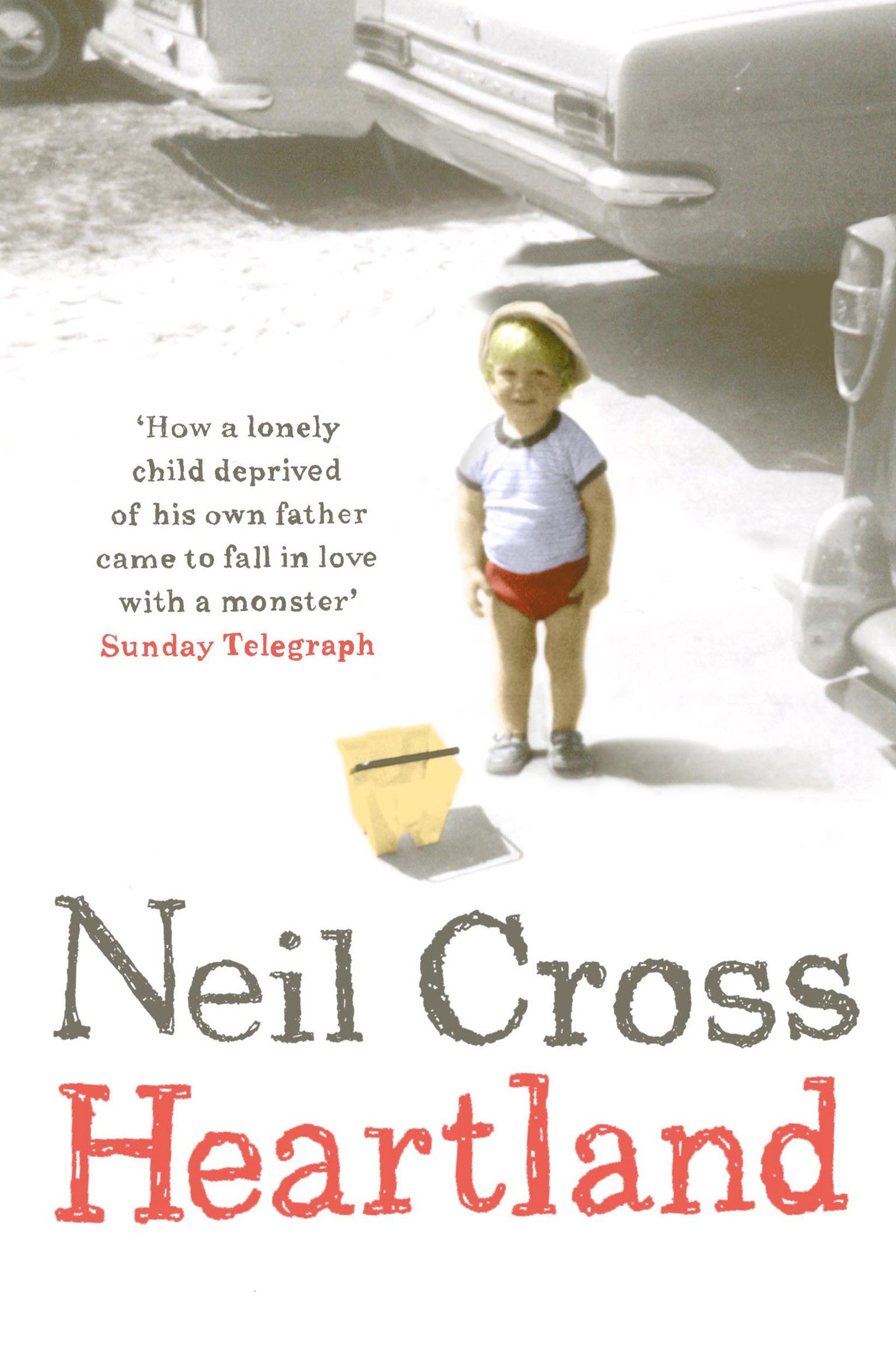

Heartland was shortlisted for the PEN/Ackerley Prize for literary autobiography 2006

When I was very young, my mother suffered a prolonged melancholy. Her post-natal depression was compounded by grief for dead children and the sorrow of a long, unhappy marriage.

In photographs taken around this time, she’s always smiling, wearing the short skirts and clunky shoes of the early 1970s, the plastic macs. Her hair is permed, dyed a harsh black. She stands on the seafront at Weston-super-Mare. I’m in the pram, a Victorian-looking thing, and I’m wearing a white, knitted cardigan with pearly buttons. My mother is

either smiling or squinting into the sun. Behind the smile, she was thinking of killing us both.

British publicity for Always the Sun had centred on the familiar question; where do your ideas come from?

This time, for once, I had a partial answer: my violently disconcerted reaction to becoming a father was related to my experience of being a son. People asked to know more, so I told them. Then I was asked to write a book about it, so I wrote one.

Heartland was never supposed to be one of those popular memoirs that trade on self-pity. Nobody with the least sense of perspective could bear to write a book like that. My childhood was pretty atypical, but I didn’t grow up hungry or cold or in a war-zone, or in a country depredated by AIDS, or violated by ideological madmen. If Heartland stands as a story — which is its job — it’s largely because of Derek Cross, the bizarre man who squats at the heart of it. Derek was capable of tremendous kindness, great hypocrisy, immense wisdom, profound idiocy, frightening selfishness, and ultimately something close to evil.

From the day I sat down to write, it became clear this book couldn’t be an act of revenge — because any reader would find that tedious. I mean, who cares? And why should I expect them to?

So I had to think of it all as a narrative, which obliged me to reflect on the motivations of the people around me, to think about why they’d behaved the way they had. Most importantly I got to imagine how it must have felt to be Derek Cross — someone who existed in a torment of dissatisfaction, a perpetual wave of self-creation and self-defacement.

The publishers wanted a quick delivery, so it was an intense, sustained effort of recall: full immersion of a kind I’d never attempted before — and wouldn‘t again, because it wasn‘t healthy.

When I began writing, I was consciously able to remember very little; five or six scenes that became cornerstones of the book, and hundreds of unconnected fragments; the shrapnel of memory. But writing memories triggered other memories, which triggered still further memories….

In the latter stages, it began to infest my dreams. I dreamed of it all night, and wrote about it all day.

It was much, much tougher than just making things up. But, having agreed to it, I had to tell the story as well as I could — even if it made me look like an idiot, a freak, or a hooligan. Which it frequently does.

US Edition: Open Road Media (December 2014)